Tortured Poets and Creative Courage: I

A literary travelogue about the iconic Dylan Thomas trail in Wales and what it taught me about creative courage: Part I

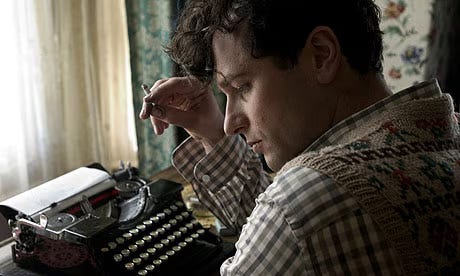

For years, as a writer, it felt like I was barking up the wrong tree. That whatever I wanted to write did not want to be written. The tortured poet in me was refusing to die but I was not able to find direction. Then I performed my poems in Aberystwyth at the Aberystwyth Poetry Festival in May 2024 and discovered that I may be a tortured poet but more than that, I was a humorous poet. If nothing else made sense in my poem about an Indian arranged marriage, at least the punchline made an audience consisting of people from of Wales, Britain, India, Asia and Europe laugh. The millennial angst was well worth the laughs accumulated that day. Still, I felt that I needed to be a serious poet. And to be a serious poet, I had to write serious poetry.

Despite this resolution, the other poems I went on to write in Aberystwyth consisted of being threatened by Seagulls for food, and imagining Godzilla-like waves in Aber. Like a religious person in moments of doubt, I wondered if visiting a shrine would absolve me of this trouble—not a Japanese Shinto Shrine or an Indian temple or a mosque or a church—I was convinced that visiting a literary shrine is the only thing that would cure me of this ailment of funny poems.

A month later, I was standing outside the door of another tortured poet, long gone, whose poems had been a great source of strength for me. This entire trip was unplanned as the most memorable adventures are. I had never planned on visiting Wales and I had surely never planned to look for someone’s grave in a Welsh town. But I did both. As the saying goes, “If the mountain will not come to Muhammad, then Muhammad must go to the mountain.”

“Do not go gentle into that good night,

…

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

—Do Not Go Gentle into that Good Night by Dylan Thomas

This poem by Welsh poet Dylan Thomas kept me going for years. I loved the lyricality of the lines, the rhythm, how the poem is at once a call to action and a source of comfort (I am not alone in wanting to give up but I must never give up). Another fellow Welshman Michael Sheen’s voice gave new life to the poem in this performance, so did Taylor Swift when she name dropped Dylan Thomas into the millennial consciousness with the lyrics of the song The Tortured Poets Department:

I suppose every Welsh person I met rolled their eyes at me whenever I mentioned wanting to visit the places on the Dylan Thomas trail. It is akin to telling every Bengali you meet how much you admire Tagore. Eye rolls will follow. But I had to be kinder to myself in this pursuit because it was my first time in Wales and I was not sure if I would ever get the chance to return. The Dylan Thomas trail consists of places where he was born and lived in Wales. Each of the towns where he lived carries a plaque signifying its historical legacy.

Even Matthew Rhys, my favourite actor, Welshman and a writer, is obsessed with Dylan Thomas … so much so that last year, he did a play on Dylan Thomas titled Dear Mr Thomas (2024) and years earlier, he portrayed Dylan Thomas in the biographical film, The Edge of Love (2008). His obsession seemed valid as Rhys was born in South Wales, same as Dylan Thomas, and grew up in a culture seeped in the writings of the poet.

I, however, was as far removed from the poet, as humanly and culturally possible. The only reason why I was obsessed with this poet was because he wrote in English his first language (despite being a Welshman, he was not taught Welsh at home) and I read him in English my fourth language and every line of his poems was seething with palpable tension that I felt in bones. He had the gift of expressing the stifling rage exceptionally well. Sometimes I wonder if he was pulling the reader out of despair by writing Do Not Go Gentle into that Good Night or himself.

I was on a day-long road trip to Cardiff with my friend and mentor, (we shall call her Professor), from Aberystwyth. She had some scheduled meetings to attend and I had the day to myself to explore Cardiff. I was most excited to see the Van Gogh paintings at the National Museum but given that it was a Monday, the museum was closed and I did not get to see any Van Gogh paintings that day. Instead, I visited Cardiff Castle, every major landmark, bookshop, cafe that was open on a weekday and bought tchotchkes at a famous comic book store. I travelled on foot and by boat. I saw the Welsh Parliament, gathered some courage and rode a roller-coaster situated by the banks of Cardiff Bay, noticed that everything was named after the lords of the Bute family (Bute Docks/Bute Street/Bute Park/Bute Town, etc.) in Cardiff, saw swans for the first time and the Wales Millennium Centre where Michael Sheen starred in the play Nye a month later, and walked up to the Norwegian Church by the bay where the popular children’s author Roald Dahl (born in Cardiff) had been baptised.

In the evening, Professor picked me up near the Millenium Centre so we could return to Aberystwyth. On the road, she mentioned that the Dylan Thomas Boathouse was located in Laugharne. If we took a short (hour-long) detour, we could visit the place. I quickly googled to check the location. The boathouse, where Dylan Thomas and his family lived from 1949 to 1953 (until his untimely death) was now a tourist attraction but it closed at 5 p.m. and so did the writing shed where Thomas used to write. Nevertheless, both of us felt that it was a now or never moment. If we had not taken the detour, I might have left without ever having visited a single place on the Dylan Thomas trail. It would not have been the end of the world but it would have meant that the literary gods had not wanted to see me that day. Little did we know …